Definition

In present day English, the word “limb” maintains its principle meaning of bodily extremities from human, animal, or non-human subjects, such as trees. The Oxford English Dictionary lists the earliest use of “limb” – sense 2, as “A part or member of an animal body distinct from the head or the trunk” – from the Blickling Homilies, c. 971: “Þa clænan leomu þære halgan fæmnan.”

Old English

As in the Blicking Homilies reference above, the Old English (OE) lim reflects extended body parts such as arms, legs, fingers, toes, and the head as well as tree branches. Latin glosses in OE sources use membra. From the Bosworth-Toller Old English Dictionary:

- OE, lim, n., often found in its plural form, leomu

- It is possible that the OE, lim, shares a root with the OE, liman, v., “to emit rays” (The verb has a secondary meaning “to join”).

Middle English

In Middle English, the term lim has several connotations beyond distinctive parts of the body. The term often evoked membership to the body of Christ. See Middle English membre. This synonymous relationship between lim and membre also grafted onto genitalia (see connotations on reproduction below). Like the OE lim, Middle English lim may conjure the image of tree branches, too. From the Middle English Dictionary:

- Middle English, lim, n. Also lime, limme, lẹ̄me, leime, and leome.

- Any distinctive constituent part or organ of the body, a member.

- (a) One of the extremities of a human or animal body excluding the head; a leg, foot, arm, hand, wing, etc.; a limb; (b) a leg of man or animal; (c) a hand; (d) one of the sexual parts of man or woman; pl.genitalia; ~ broke, affected with scrotal hernia, ruptured.

- In phrases: (a) ech (a) ~, in every part of the body, all over; lippe and ~, ~ and hed, all parts of the body; peine of ~ and lond, penalty of mutilation and loss of land; (b) bothe in lith and ~, bothe) ~ and lith, bothe) lith and ~, everi ~ and lith, in (of) ~ and lith, in (of) lith and ~, lith nor ~, nother lith nor ~, with ~ and lith[see lithn. (1) (f)]; fro lith to ~ [see lith n. (1) (a)]; (c) ~ from ~, limb from limb; heuen (renden, tolithen) ~ from other, to cut or tear one limb from another; riven (toriven) ~ from ~, dismember (sb.); drauen (renden) ~ from (for) ~, fig. dismember God or Christ with oaths on parts of the body; (d) lif and ~, ~ and lif [see lif n. 1c. (d)].

- (a) A Christian or good man considered as a member of the body of Christ; cristes ~, ~ of crist (holi chirche, the regne of god); also, by analogy, a follower or agent of the devil, a heathen, a sinner; antecristes ~, develes ~, fendes ~, ~ of satanas (antecrist, the fend); (b) a social dependent, a liegeman; (c) hores ~, a follower of whores; theves ~, a member of the thieving fraternity.

- Miscel. senses: (a) a branch or part of a subject of discourse; (b) a sea that flows into the ocean, an arm of the sea; (c) a projecting corner of a siege tower.

- Related to Middle English lim:

- Middle English, limbe, n. from Old French, limbe and Latin limbus

- The graduated edge or border of an equatorie; (b) the land bordering a river; (c) = limbo, q.v.; helles ~; ~ of fadres, the limbus patrum.

- Middle English, lom(e, from Old English, loma

- An implement or tool, a loom for weaving, figuratively, a weapon, a penis

- In its entry on “limb, 1” Etymonline writes that “the unetymological –b in limb began to appear late 1500s for no etymological reason” but may have been influenced by the word’s cognate limp, v. “to move with a jerky step.” In Middle English, lympen means “to fall short,” and modern German lampen means “to hang limp” (Middle High German limphin). The connection between limb and limp may be from an old Proto Indo-European root that meant “to hang loosely” (see Sanskrit lambate “hangs down” and Middle High German lampen “to hang down”).

- See also OE limpan, v. “to befall, happen”

- Middle English, limbe, n. from Old French, limbe and Latin limbus

Related terms

Latin: The Latin terms membra and limbus gloss the Middle English lim and limbe respectively.

Old Norse: The Old Norse (ON) limr conveyed both human limbs (for instance in the common ON idiom halda lífi ok limum, “to have life and limb”) and joints of meat.

Old/Early Scots: The Old Scots lim or lym refers to organs or parts of the human or animal body as well as a joint of meat. For instance, The Brus reads, “Bot off lymmys he wes weill maid, / With banys gret & schuldrys braid” (l. 385).

German: Glied, “member,” “joint,” “limb,” “link,” “penis”

Old Frisian: lith, “limb”

Gothic: liþus, “limb”

Story

For many medieval Christians, the symbolic weight of the limb was bound up in the Christological division of the body. Christ acted as the head of the Christian community’s body, while all good Christians made up the members, or limbs, of the body. Perhaps most influentially, the First Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians outlines the membered body analogy as it relates to the body of the Church.[1] St. Paul analogizes a community of faith through the image of the body:

sicut enim corpus unum est et membra habet multa omnia autem membra corporis cum sint multa unum corpus sunt ita et Christus etenim in uno Spiritu omnes nos in unum corpus baptizati sumus sive Iudaei sive gentiles sive servi sive liberi et omnes unum Spiritum potati sumus nam et corpus non est unum membrum sed multa. Si dixerit pes quoniam non sum manus non sum de corpore non ideo non est de corpore et si dixerit auris quia non sum oculus non sum de corpore si totum corpus oculus ubi auditus si totum auditus ubi odoratus nunc autem posuit Deus membra unumquodque eorum in corpore sicut voluit quod si essent omnia unum membrum ubi corpus nunc autem multa quidem membra unum autem corpus[2]

Just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ. For we were all baptized by one Spirit so as to form one body – whether Jews or Gentiles, slave or free – and we were all given the one Spirit to drink. Even so the body is not made up of one part but of many. Now if the foot should say, “Because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason cease to be part of the body. And if the ear should say, “Because I am not an eye, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason cease to be part of the body. If the whole body were an eye, where would the sense of hearing be? If the whole body were an ear, where would the sense of smell be? But in fact God has placed the parts in the body, every one of them, just as he wanted them to be. If they were all one part, where would the body be? As it is, there are many parts, but one body.[3]

This ubiquitous image of the Christian body of members was taken up anew by John of Salisbury in his Policraticus, a work that translated this Christological physiognomy into legal theory. The Policraticus articulated what became known as the medieval “body politic,” where the king acted as the head rather than Christ, and the laborers were the limbs of the body. An imagined “wholeness” of a community made up from distinct parts dominated much of medieval Christian ideology. Caroline Walker Bynum’s work on fragmentation has shown that twelfth- and thirteenth-century theological debates center on the eucharist and transubstantiation, the relationship between body and soul, and new regulations on miracles, relics, and the mediation of the body. This religious landscape transformed ideas about the partition of the body, which, as Bynum puts it, whether through “reunion of parts into a whole or through assertion of part as part to be the whole – was the image of paradise.”[4]

Limbs were also featured in medical treatises such as Guy de Chauliac’s Chirurgia magna, c. 14th century. Typically, medieval medical language would use the term membre rather than lim, as in the heading to the second part of the Chirurgia magna, which reads “And begynneth the seconde ptycle / where as is moued & assysed certayne questions and difficultees vpon the Anathomy of the membres composed.” Similarly, in John of Arderne’s Tretis of fistula in ano, the second tract discusses fistula in the limbs, but rather than using the term lim, Arderne’s Tretis divides the limbs into parts. For instance, Tretis 2.8 is headed “Of fistul in þe lawe ioyntour of þe fyngers, and in þe legges, knees, fete, & ankles, wiþ corruptyng of þe bones, and þe hardnes of þe cure.” Here Arderne counts all the lower limbs under the title “lawe ioyntour” – the lower joints of the body.

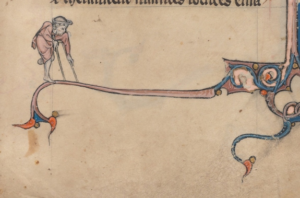

The limb had a peculiar function in material, textual culture as well. Scribes also used manicula, (Latin: “little hand”) to point to important aspects of a text. These were small floating hands and fingers, sometimes attached to an entire body (either human, animal, or otherwise), that were used as teaching tools. Essentially, medieval sticky notes.

Evidence and Images

Image of the well-known medieval story, “Miracle of a Black Leg.” Sts. Cosmas and Damian, ca. 1370–75, Master of the Rinuccini Chapel (Matteo di Pacino) (Italian, active 1350–75), tempera and gold leaf on panel. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh

Image of an individual with prosthetic walking devices. Yale University, Beinecke MS 229, f.108r 13th century.

Image of a “manicule” in the Maastricht Psalter. British Library Stowe 17, f193r, 14th century.

Further Reading

Beckwith, Sarah. Christ’s Body: Identity, Culture, and Society in Late Medieval Writings. (Routledge, 1996).

Bynum, Caroline Walker. Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion. New York: Urzone Publishers, 1991.

Etymonline: “limb” (n.1): https://www.etymonline.com/word/limb

Gianfalla, Jennifer M. “‘Ther is moore mysshapen amonges thise beggares,’: Discourses of Disability in Piers Plowman,” in Disability in the Middle Ages: Reconsiderations and Reverberations. ed. Joshua R. Eyler. (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010): 119-134.

Jović, Nebojša J. and Marios Theologou, “The Miracle of the Black Leg: Eastern Neglect of Western Addition to the Hagiography of Saints Cosmas and Damian,” Acta Med Hist Adriat 13.2 (2015): 329-344.

Metzler, Irina. A Social History of Disability in the Middle Ages: Cultural Considerations of Physical Impairment. London: Routledge, 2013.

One Leg in the Grave Revisited: The Miracle of the Transplantation of the Black Leg by the Saints Cosmas and Damian. ed. Kees Zimmerman. (Groningen: Barkhuis, 2013).

“The Story of the Little Pointing Hand Symbol,” BBC Ideas 2018: https://www.bbc.com/ideas/videos/the-story-of-the-little-pointing-hand-symbol/p0696z72

Walter, Katie L. “Fragments for a Medieval Theory of Prosthesis,” Textual Practice 30.7 (2016): 1345-1363.

Contributor

Micah James Goodrich, University of Connecticut

[1] See also Romans 12:5 and Ephesians 4.

[2] 1 Corinthians 12:12-20. See Biblia Sacra: Iuxta Vulgatam Versionem. ed. Robert Weber. (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1969).

[3] The Writings of St. Paul, eds. Wayne A. Meeks and John T. Fitzgerald. 2nd edition. (New York: Norton, 2007): 38.

[4] Caroline Walker Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion. (New York: Zone Books, 1992): 13.